Elizabeth Blackwell (1821 – 1910)

Elizabeth Blackwell was born in 1821 in Bristol, England. When she was 11 years old, her family moved to America to assist in abolishing slavery. As a young girl, she took interest in history and physics and cringed at the sight of medical books. She changed her studies after a close friend died. Friends and family were weary of her decision because of how difficult and expensive medical school would be and that it was not available for women. Through the year, Blackwell read medical books with physicians and applied to as many medical schools as she could. She was accepted into Geneva Medical School in 1847. Two years after her acceptance, Blackwell was the first woman to graduate medical school with and M.D. degree from an American institute. She then moved back to Europe where she worked in clinics and studied midwifery. In 1851, she returned to America after she lost eyesight in one eye. In the states, she established a practice in New York City. in 1856, Blackwell, her sister, and Dr. Marie Zakrzewska opened the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, where women would be able to study medicine and become doctors.

Source: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_35.html

Alice Marie Coachman (1923 – 2014)

Alice Coachman was the first black woman from any country to win an Olympic Gold medal. She won her medal in the high jump for the United States in 1948 at the London Olympics. She was not allowed to train at athletic fields with whites, so she would use ropes and sticks as high jumps while she ran barefoot. Coachman was the first black person to receive an international endorsement deal when Coca-Cola signed her as a spokesperson in 1952. She was quoted in the New York Times in 1996 as saying, “If I had gone to the Games and failed, there wouldn’t be anyone to follow in my footsteps. It encouraged the rest of the women to work harder and fight harder,” She paved the way for African-American athletes such as Wilma Rudolph, Evelyn Ashford, Florence Griffith Joyner, and many others. She finished her track and field career as a teacher and track-and-field instructor. Coachman was inducted into nine hall of fames including the National Track-and-Field Hall of Fame (1975) and the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame (2004).

Alice Coachman was the first black woman from any country to win an Olympic Gold medal. She won her medal in the high jump for the United States in 1948 at the London Olympics. She was not allowed to train at athletic fields with whites, so she would use ropes and sticks as high jumps while she ran barefoot. Coachman was the first black person to receive an international endorsement deal when Coca-Cola signed her as a spokesperson in 1952. She was quoted in the New York Times in 1996 as saying, “If I had gone to the Games and failed, there wouldn’t be anyone to follow in my footsteps. It encouraged the rest of the women to work harder and fight harder,” She paved the way for African-American athletes such as Wilma Rudolph, Evelyn Ashford, Florence Griffith Joyner, and many others. She finished her track and field career as a teacher and track-and-field instructor. Coachman was inducted into nine hall of fames including the National Track-and-Field Hall of Fame (1975) and the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame (2004).

Source: Barry, Sara. “15 Important Women in History You May Not Have Heard Of.” Explore the Archive,8 Nov. 2017, www.explorethearchive.com/15-women-in-history.

Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958)

Born in 1920 in London, Rosalind Franklin pioneered the use of x-rays to study DNA. Her breakthrough photographs would change the future of biology. She is well-known for having been shamefully robbed of credit for her research. Franklin graduated with a doctorate in physical chemistry from Cambridge University in 1945, then spent three years at an institute in Paris where she learned x-ray diffraction techniques, or the ability to determine the molecular structures of crystals. She returned to England in 1951 as a research associate in John Randall’s laboratory at King’s College in London and soon encountered Maurice Wilkins, who was leading his own research group studying the structure of DNA. Franklin and Wilkins worked on separate DNA projects, but mistakenly Wilkins mistook Franklin’s role in Randall’s lab as that of an assistant rather than head of her own project. Meanwhile, James Watson and Francis Crick, both at Cambridge University, were also trying to determine the structure of DNA. They communicated with Wilkins, who at some point showed them Franklin’s images of DNA – known as Photo 51—without her knowledge. Photo 51 enabled Watson, Crick, and Wilkins to deduce the correct structure for DNA, which they published in a series of articles in the journal Nature in April 1953. Franklin also published in the same issue, providing further details on DNA’s structure. Franklin’s image of the DNA molecule was key to deciphering its structure, but only Watson, Crick, and Wilkins received the 1962 Nobel Prize in physiology/medicine for their work. Franklin died of ovarian cancer in 1958 in London, four years before Watson, Crick, and Wilkins received the Nobel. Since Nobel prizes aren’t awarded posthumously, we’ll never know whether Franklin would have received a share in the prize for her work.

Born in 1920 in London, Rosalind Franklin pioneered the use of x-rays to study DNA. Her breakthrough photographs would change the future of biology. She is well-known for having been shamefully robbed of credit for her research. Franklin graduated with a doctorate in physical chemistry from Cambridge University in 1945, then spent three years at an institute in Paris where she learned x-ray diffraction techniques, or the ability to determine the molecular structures of crystals. She returned to England in 1951 as a research associate in John Randall’s laboratory at King’s College in London and soon encountered Maurice Wilkins, who was leading his own research group studying the structure of DNA. Franklin and Wilkins worked on separate DNA projects, but mistakenly Wilkins mistook Franklin’s role in Randall’s lab as that of an assistant rather than head of her own project. Meanwhile, James Watson and Francis Crick, both at Cambridge University, were also trying to determine the structure of DNA. They communicated with Wilkins, who at some point showed them Franklin’s images of DNA – known as Photo 51—without her knowledge. Photo 51 enabled Watson, Crick, and Wilkins to deduce the correct structure for DNA, which they published in a series of articles in the journal Nature in April 1953. Franklin also published in the same issue, providing further details on DNA’s structure. Franklin’s image of the DNA molecule was key to deciphering its structure, but only Watson, Crick, and Wilkins received the 1962 Nobel Prize in physiology/medicine for their work. Franklin died of ovarian cancer in 1958 in London, four years before Watson, Crick, and Wilkins received the Nobel. Since Nobel prizes aren’t awarded posthumously, we’ll never know whether Franklin would have received a share in the prize for her work.

Source: https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/13/130519-women-scientists-overlooked-dna-history-science/

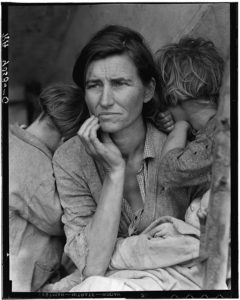

Florence Owens Thompson (1903-1983)

This photograph is one of the most iconic photographs of the Great Depression. It has become known as “Migrant Mother” and serves as one of a series of photographs that Dorothea Lange made of Florence Owens Thompson and her children in February or March of 1936 in Nipomo, California. Lange was concluding a month’s trip photographing migratory farm labor around the state for what was then the Resettlement Administration. Lange notices that Thompson appeared hungry and desperate. The subject asked no questions and offered very little of her plight. She stated that she was 32 with five kids and had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean- to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me.

This photograph is one of the most iconic photographs of the Great Depression. It has become known as “Migrant Mother” and serves as one of a series of photographs that Dorothea Lange made of Florence Owens Thompson and her children in February or March of 1936 in Nipomo, California. Lange was concluding a month’s trip photographing migratory farm labor around the state for what was then the Resettlement Administration. Lange notices that Thompson appeared hungry and desperate. The subject asked no questions and offered very little of her plight. She stated that she was 32 with five kids and had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean- to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me.

Source: http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/fsa.8b29516/

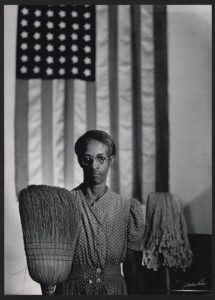

Ella Watson

This famed photograph called American Gothic, Washington, D.C., 1942 was taken by famed African American photographer Gordon Parks. He pioneered documentary journalism for over forty years, focusing on issues of civil rights and poverty. Parks year-long fellowship with the Information Division of the Farm Security Administration in 1942 supported his work documenting black lives in Washington, D.C. He later said this photograph, a portrait of government cleaning woman Ella Watson was meant to portray the kind of bigotry and discrimination here that I never expected to experience in the nation’s capital. Parks wanted to depict the efforts of a black woman at work that many people see as invisible. So he put Ella before the American flag with a broom in one hand and a mop in another. And I said,”American Gothic—that’s how I felt at the moment.” Ella supported her family of six on a salary of $1080 per year. During WWII she devoted over ten percent of her wages to war bonds.

Source: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.05809/ and https://collections.artsmia.org/art/100557/american-gothic-washington-d-c-gordon-parks